Greyhound Welfare

Welfare of a Greyhound used to race

Disadvantages

Over the last few decades multiple cases concerning Greyhound cruelty and slaughter have been documented.

Use of class A drugs, amphetamines and steroids being administered to dogs in order to fix races. (Side effects of doping include organ damage and death).

Dogs confined to dirty kennels/sheds, with no light, poor ventilation, no heating, poor bedding.

Masses of dogs killed by use of the Captive bolt gun on private land and in abattoirs

Dogs destroyed by the stadium vet for minor injuries

Dogs reported by former greyhound trainer as being shot by local huntsmen

Dogs found mutilated, neglected or dead, dumped across the country

(Dogs sometimes have their ears mutilated, cut off with a knife or scissors to prevent them being traced back to the owner via the ear tattoo)

Dogs kept confined to sheds on allotments or kennels where they are hoarded when no longer of use for racing

Greyhounds exported to Pakistan, India, Spain, China and many other countries where there are little or no animal welfare laws to protect them.

Breeding

83% of Greyhounds raced in Britain are bred in Ireland and transported to the UK on a supply and demand basis. The fastest and fittest dogs are in high demand, these dogs are less likely to be destroyed for a minor injury as they can used for breeding purposes due to their good genetics/bloodline and speed. The slow or unhealthy dogs are less of a requirement and are easily discarded of, this includes the mental ability of a dog i.e Dogs that are not compatible with other dogs, may fight on the track, rendering the dog unsuitable to perform on the track.

Dogs that are often disposed of due to

NOT being commercially viable.

• Too Slow

• Unhealthy

• Little or no interest in running

• Pregnant

• Injury

• Not compatible with other dogs

Injuries

• Around 5000 dogs are injured on licensed UK tracks annually.

• Dogs are often made to run in freezing cold icy weather conditions & also extreme hot weather conditions of up to 34 degrees Celsius

• The stadium vet can destroy a dog at a stadium for minor injuries depending

on the decision of the owner/trainer

• Every stadium has a freezer to store dead dogs

• It often costs less for the stadium vet to destroy a dog than to pay a private vet

• No insurance company will insure a Greyhound used to race on the track

Over the last few decades multiple cases concerning Greyhound cruelty and slaughter have been documented.

Use of class A drugs, amphetamines and steroids being administered to dogs in order to fix races. (Side effects of doping include organ damage and death).

Dogs confined to dirty kennels/sheds, with no light, poor ventilation, no heating, poor bedding.

Masses of dogs killed by use of the Captive bolt gun on private land and in abattoirs

Dogs destroyed by the stadium vet for minor injuries

Dogs reported by former greyhound trainer as being shot by local huntsmen

Dogs found mutilated, neglected or dead, dumped across the country

(Dogs sometimes have their ears mutilated, cut off with a knife or scissors to prevent them being traced back to the owner via the ear tattoo)

Dogs kept confined to sheds on allotments or kennels where they are hoarded when no longer of use for racing

Greyhounds exported to Pakistan, India, Spain, China and many other countries where there are little or no animal welfare laws to protect them.

Breeding

83% of Greyhounds raced in Britain are bred in Ireland and transported to the UK on a supply and demand basis. The fastest and fittest dogs are in high demand, these dogs are less likely to be destroyed for a minor injury as they can used for breeding purposes due to their good genetics/bloodline and speed. The slow or unhealthy dogs are less of a requirement and are easily discarded of, this includes the mental ability of a dog i.e Dogs that are not compatible with other dogs, may fight on the track, rendering the dog unsuitable to perform on the track.

Dogs that are often disposed of due to

NOT being commercially viable.

• Too Slow

• Unhealthy

• Little or no interest in running

• Pregnant

• Injury

• Not compatible with other dogs

Injuries

• Around 5000 dogs are injured on licensed UK tracks annually.

• Dogs are often made to run in freezing cold icy weather conditions & also extreme hot weather conditions of up to 34 degrees Celsius

• The stadium vet can destroy a dog at a stadium for minor injuries depending

on the decision of the owner/trainer

• Every stadium has a freezer to store dead dogs

• It often costs less for the stadium vet to destroy a dog than to pay a private vet

• No insurance company will insure a Greyhound used to race on the track

Re-homing

A minority of the dogs are re-homed

• Some dogs are re-homed to independent rescue centre's who do NOT receive any government funding

• Some dogs are re-homed to GBGB certified rescues who receive funding from the Greyhound Racing Industry itself, rather than opting to be independent and publicly funded. 'Fully independent rescues are able to openly air their concerns around greyhound cruelty'

The Greyhound Trust (GT) was originally set up by the Greyhound racing industry at a time when public concern was raised as to what was happening to the dogs when they ended their racing days. Many Campaigners and advocates tend to view the GT as a public relations team, working with the industry to appease the public.

Whilst it is claimed that the new rehoming scheme for greyhounds is successful;

1) Dogs are advertised on Gumtree and other free internet advertising websites

2) Dogs are found abandoned

3) Dogs are euthanized by a vet

4) Dogs can be legally killed by Captive bolt gun

5) Dogs may be killed by other means.

6) Dogs are exported overseas to numerous countries where there are no animal welfare laws to protect greyhounds, such as Spain, Pakistan and China.

Re: no 4 & 5

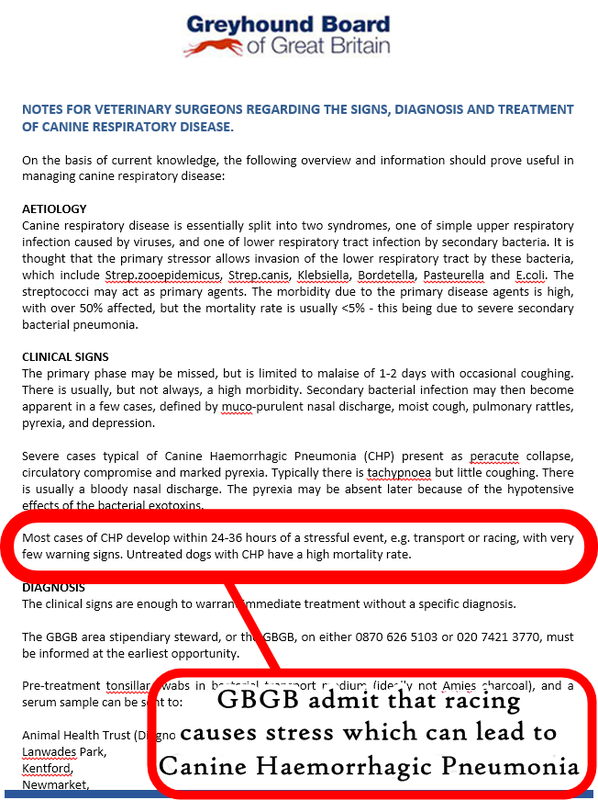

AWA2006 States it is an offence to cause pain and suffering to an animal. An offence has to be proven before a person will be charged for unlawfully killing an animal. The Greyhound Racing industry is self governed by the Greyhound Board of Great Britain (GBGB) If cruelty is reported to the RSPCA regarding suffering of a Greyhound that is still registered to race, the RSPCA will usually pass the case on to the GBGB and vice versa.

Please note: The AWA 2006 depends on local authorities employing warranted officers to enforce the act. As far as we are aware only a handful of local authorities employ a warranted officer.

The breed of Greyhound has existed for thousands of years and Greyhound racing has only existed in the UK since 1926.

Greyhounds make excellent loyal companions and were once very highly respected but nowadays they are often discarded like trash.

A minority of the dogs are re-homed

• Some dogs are re-homed to independent rescue centre's who do NOT receive any government funding

• Some dogs are re-homed to GBGB certified rescues who receive funding from the Greyhound Racing Industry itself, rather than opting to be independent and publicly funded. 'Fully independent rescues are able to openly air their concerns around greyhound cruelty'

The Greyhound Trust (GT) was originally set up by the Greyhound racing industry at a time when public concern was raised as to what was happening to the dogs when they ended their racing days. Many Campaigners and advocates tend to view the GT as a public relations team, working with the industry to appease the public.

Whilst it is claimed that the new rehoming scheme for greyhounds is successful;

1) Dogs are advertised on Gumtree and other free internet advertising websites

2) Dogs are found abandoned

3) Dogs are euthanized by a vet

4) Dogs can be legally killed by Captive bolt gun

5) Dogs may be killed by other means.

6) Dogs are exported overseas to numerous countries where there are no animal welfare laws to protect greyhounds, such as Spain, Pakistan and China.

Re: no 4 & 5

AWA2006 States it is an offence to cause pain and suffering to an animal. An offence has to be proven before a person will be charged for unlawfully killing an animal. The Greyhound Racing industry is self governed by the Greyhound Board of Great Britain (GBGB) If cruelty is reported to the RSPCA regarding suffering of a Greyhound that is still registered to race, the RSPCA will usually pass the case on to the GBGB and vice versa.

Please note: The AWA 2006 depends on local authorities employing warranted officers to enforce the act. As far as we are aware only a handful of local authorities employ a warranted officer.

The breed of Greyhound has existed for thousands of years and Greyhound racing has only existed in the UK since 1926.

Greyhounds make excellent loyal companions and were once very highly respected but nowadays they are often discarded like trash.

ADVANTAGES = NONE

GREYHOUND CADAVERS DONATED BY THE INDUSTRY FOR RESEARCH (AU)

Personal Reflections on Veterinary Science Training and the Three Rs, Rosemary Elliott. Students against the thoughtless use of animals

In veterinary education need support

to be true to their values, to use

science to uphold them, and to never

give up on advocating for the

highest standards of animal welfare.

This opinion piece is something I needed to write personally, and it shocks me to notice the ten years that have passed since I enrolled as a mature-age student in veterinary science. It was a privilege to have this opportunity, and I am grateful that I can now advocate for animals in a way I never could have done before, particularly through my work with Sentient. By the time I enrolled in veterinary science, the faculty where I studied had made huge advances in the ethical use of animals in teaching, most notably through the banning of ‘terminal surgeries’. Since my time as a student, things have improved even more, and the faculty is leading the way in developing a national curriculum for animal welfare and ethics in veterinary teaching. Yet, despite this, some attitudes and practices ‘die hard’, and many of my experiences could only be described as vicarious trauma — hence the passing of so much time before I felt ready to give life to them with words.

Although the animals I speak of were used primarily for educational purposes, I do hope that those of you working in the laboratory setting with research animals, will find that my reflections will stimulate your own thinking and resonate with some of your experiences. We have much in common in our struggle to do our work and to do the best we can by the animals in our care.

Anatomy classes

Admittedly, I grew up with an idealised view of veterinary practice, starting with Dr Doolittle as a very small child, then moving on to All Creatures Great and Small and the other James Herriot books. Although 60 years had passed since the setting of those stories, with the onset of intensive farming, I went on assuming it was primarily about supportive teamwork and above all, empathy for animals.

The first wake-up call came in the form of Anatomy 1A. The laboratory, a huge room with grimacing dead greyhounds lying on metal trays, became a hothouse of anxieties, sometimes played out by the larking about that involved the throwing of body parts. The smell of formalin was so powerful that I can still conjure it up. In groups of three or four, we learned anatomy the traditional way, which some of us described as “being thrown a dead dog and a textbook”. There was minimal instruction, so we were left to hack away in the pursuit of identifying a lengthy page of anatomical features, ‘all examinable’, with the pressure to clean up before our class ended.

I don’t remember being told why they were always greyhounds, or how they were sourced. There was certainly no time for debriefing, and we learned early on that it was unacceptable to appear emotional. I soon became desensitised to this horrible scene until the 4th year, when I was initiated into surgical training on freshly-killed pound dogs of various breeds — soft and floppy and somehow, not being greyhounds, they seemed more individual, more like pets. I remember struggling with sad moments of wondering about their lives and whether they had been loved, and feeling ashamed of my tacit acceptance of greyhounds as production animals.

Now, this raises for me the question of respect for life, even after a life is over. If we are serious about honouring the dignity of animals and safeguarding their welfare, veterinary training must provide as many opportunities as possible for effective learning that reduces the number of animals used, such as initial skills training through videos and silicone simulator anatomical models. At Sentient, we also call for the veterinary profession to supply cadavers from ethical sources, rather than colluding with the widespread disposal of racing greyhounds by ‘convenience euthanasia’.

Thank you to Rosemary Elliott & Editor Susan Trigwell for allowing us to use this extract.

http://pilas.org.uk/personal-reflections-on-veterinary-science-training-and-the-three-rs/

In veterinary education need support

to be true to their values, to use

science to uphold them, and to never

give up on advocating for the

highest standards of animal welfare.

This opinion piece is something I needed to write personally, and it shocks me to notice the ten years that have passed since I enrolled as a mature-age student in veterinary science. It was a privilege to have this opportunity, and I am grateful that I can now advocate for animals in a way I never could have done before, particularly through my work with Sentient. By the time I enrolled in veterinary science, the faculty where I studied had made huge advances in the ethical use of animals in teaching, most notably through the banning of ‘terminal surgeries’. Since my time as a student, things have improved even more, and the faculty is leading the way in developing a national curriculum for animal welfare and ethics in veterinary teaching. Yet, despite this, some attitudes and practices ‘die hard’, and many of my experiences could only be described as vicarious trauma — hence the passing of so much time before I felt ready to give life to them with words.

Although the animals I speak of were used primarily for educational purposes, I do hope that those of you working in the laboratory setting with research animals, will find that my reflections will stimulate your own thinking and resonate with some of your experiences. We have much in common in our struggle to do our work and to do the best we can by the animals in our care.

Anatomy classes

Admittedly, I grew up with an idealised view of veterinary practice, starting with Dr Doolittle as a very small child, then moving on to All Creatures Great and Small and the other James Herriot books. Although 60 years had passed since the setting of those stories, with the onset of intensive farming, I went on assuming it was primarily about supportive teamwork and above all, empathy for animals.

The first wake-up call came in the form of Anatomy 1A. The laboratory, a huge room with grimacing dead greyhounds lying on metal trays, became a hothouse of anxieties, sometimes played out by the larking about that involved the throwing of body parts. The smell of formalin was so powerful that I can still conjure it up. In groups of three or four, we learned anatomy the traditional way, which some of us described as “being thrown a dead dog and a textbook”. There was minimal instruction, so we were left to hack away in the pursuit of identifying a lengthy page of anatomical features, ‘all examinable’, with the pressure to clean up before our class ended.

I don’t remember being told why they were always greyhounds, or how they were sourced. There was certainly no time for debriefing, and we learned early on that it was unacceptable to appear emotional. I soon became desensitised to this horrible scene until the 4th year, when I was initiated into surgical training on freshly-killed pound dogs of various breeds — soft and floppy and somehow, not being greyhounds, they seemed more individual, more like pets. I remember struggling with sad moments of wondering about their lives and whether they had been loved, and feeling ashamed of my tacit acceptance of greyhounds as production animals.

Now, this raises for me the question of respect for life, even after a life is over. If we are serious about honouring the dignity of animals and safeguarding their welfare, veterinary training must provide as many opportunities as possible for effective learning that reduces the number of animals used, such as initial skills training through videos and silicone simulator anatomical models. At Sentient, we also call for the veterinary profession to supply cadavers from ethical sources, rather than colluding with the widespread disposal of racing greyhounds by ‘convenience euthanasia’.

Thank you to Rosemary Elliott & Editor Susan Trigwell for allowing us to use this extract.

http://pilas.org.uk/personal-reflections-on-veterinary-science-training-and-the-three-rs/